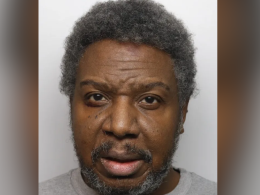

A 20-year-old man has been jailed for life with a minimum term of 23 years for murdering a 16-year-old Syrian refugee in a daylight attack on a busy Huddersfield shopping street, after the boy brushed past the man’s girlfriend. Sentencing at Leeds Crown Court, Judge Howard Crowson told Alfie Franco that CCTV showed he was “under no threat whatsoever” when he opened a flick knife and drove it into the neck of Ahmad Al Ibrahim, an unarmed teenager who had arrived in the UK only weeks earlier after fleeing war in Homs. The judge rejected Franco’s claim that he acted in self-defence, calling it “a lie,” and said the defendant had “identified him as a target and lured him to within your range to strike before killing him,” deliberately aiming for the neck. Jurors convicted Franco on Thursday after a six-day trial; he had pleaded guilty to possessing a knife in public but denied murder.

The court heard that on the afternoon of 3 April, Franco was walking with his girlfriend after a Jobcentre appointment and told jurors he was on his way to buy eyelash glue. Ahmad, out with a friend, passed by the couple near Ramsden Street. Prosecutor Richard Wright KC said Franco took “some petty exception” to the teenager “innocuously” walking past his girlfriend. CCTV footage, played to the court, showed Franco calling out to Ahmad after a brief exchange of words. As the boy approached, Franco slipped a flick knife from his waistband, opened it and kept it concealed at his side before lunging once, striking Ahmad in the neck. The teenager staggered a short distance, clutching at his throat, and collapsed. He suffered catastrophic injuries and died at the scene despite rapid efforts to save him.

Toxicology testing showed Franco had recently consumed cannabis, cocaine, diazepam, ketamine and codeine. The prosecutor told jurors that, far from being panicked, Franco could be seen on the footage “cool as a cucumber” during the confrontation, at one stage calmly eating an ice cream while preparing the weapon. “To plunge that knife into someone’s neck who has done no more than walk towards you after you’ve engaged them in some verbal argy-bargy in the street… that’s not reasonable self-defence,” Wright told the jury. He described the defendant as “a young man with a cocky swagger… on drugs, who doesn’t like the fact that Ahmad has spoken back to him.”

Franco maintained from the witness box that he thought he saw Ahmad reaching for a weapon in his waistband and that he had aimed for the boy’s cheek intending to “cut him and get away,” an account the judge said the video contradicted in every material respect. “Before Ahmad made any movement towards you, you prepared your knife for use,” Judge Crowson said in his remarks. “You calmly and surreptitiously removed the knife from your waistband, opened it and concealed it in your pocket.” He added that he was satisfied Franco intended to kill. “Ahmad was unarmed as he walked peacefully about Huddersfield town centre that day.”

Police and prosecutors said the attack was unprovoked and that Franco’s conduct before and after the stabbing undermined his claim to have been frightened. West Yorkshire Police said detectives never accepted that self-defence was plausible, pointing to the CCTV chronology and to the fact that the only weapon present was the flick knife Franco had chosen to carry. Temporary Detective Superintendent Damian Roebuck, who led the investigation, called the killing “a dreadful and inexplicable murder of a teenager he had never met and who he had no quarrel with,” and said he hoped the sentence would bring “some measure of comfort” to a grieving family.

Ahmad’s relatives described a gentle and ambitious boy who dreamed of becoming a doctor and had spoken of wanting “to heal others after all he had endured.” In a statement read in court, his uncle, Ghazwan Al Ibrahim, said the teenager had spent three months travelling to Britain, first staying in a Home Office hotel for young people in Swansea before moving to Huddersfield to live nearby. He had been in the town for only a couple of weeks and was making one of his first trips into the centre alone when he was killed. “He had a sociable and ambitious personality, loved helping people and was passionate about life,” the statement said, adding that Ahmad believed the UK was “the land of peace and the fulfilment of dreams.” His parents, who remained in Syria, contributed to the family statement; the court heard his father suffered a heart attack on receiving news of his son’s death and required surgery. “I am unable to describe the impact of their heinous crime and the impact it had over everyone,” the statement said. “His mother still cries over his clothes as they smell of him.”

The trial examined Franco’s movements in the moments before the stabbing and his interest in knives. Jurors were told he had recorded himself handling the same flick knife used in the killing and had shared images of a small collection captioned “Artillery coming along nice.” The court heard he had sent a message threatening to stab someone in an unrelated dispute over a stolen pushbike. Prosecutors said those details were not presented to suggest bad character in general but to rebut any suggestion the knife was carried for protection or that Franco’s use of it was momentary or impulsive. The defence said he feared for his safety when he saw Ahmad and his friend, insisting that the movement at the waistband made him think a weapon was being drawn. The CCTV, which the prosecution said captured Franco opening the blade before he summoned Ahmad closer, was decisive.

Judge Crowson told Franco that the coldness of his preparation and the targeting of the neck made the killing particularly grave. “You identified him as a target,” he said. “You lured him to within your range to strike… you deliberately aimed for the neck.” The judge referenced the efforts of medics who fought to save the boy, saying it was “a testament to the medical personnel trying to save his life and his will to live” that Ahmad “even made it to the hospital alive, but in truth his wounds were unsurvivable.” The life sentence with a 23-year minimum term reflects the court’s assessment of culpability given the use of a knife in public, the choice of a vulnerable area and the lack of any provocation that could mitigate the attack.

In his closing speech, Wright said the stabbing was the culmination of petty resentment. “This is a case of a young man… who doesn’t like the fact that Ahmad has spoken back to him,” he told jurors, urging them to focus on the footage and the single, devastating blow that followed Franco’s beckoning gesture. After the attack, Franco fled the scene; he later handed himself in to police and was charged. Throughout the trial he denied murder, but the jury deliberated only a few hours before returning a unanimous guilty verdict.

Ahmad’s story, recounted in court by relatives and by those who first knew him in Britain, struck a stark contrast with the manner of his death. Injured in a bombing in Homs, he had left Syria as an unaccompanied child, according to evidence heard by the court, and reached the UK after a months-long journey through Europe. He enrolled in college in Swansea while awaiting a permanent placement, then moved to West Yorkshire to be near his uncle. Family members said he treated the move as a fresh start and talked frequently about studying medicine. On the day of the killing he was taking one of his first solo walks around the centre of Huddersfield, excited about finding his way in a new town.

The case has amplified local concern about knife crime and about the ease with which small, concealable blades can be carried into crowded spaces. Police said the murder investigation drew on extensive town-centre camera coverage and eyewitness testimony, and that public video captured the central sequence: a brief verbal exchange, a beckoning gesture, the hidden motion of a blade being prepared, and the single, fatal strike. Officers said they would continue prevention work with schools and community groups in West Yorkshire focused on carrying knives, hardening the message that the risk they pose to others—and to the carrier, who may face life imprisonment for a moment’s eruption—far outweighs any perceived protection.

For Ahmad’s family, the sentence closed only the legal chapter. Outside court, his uncle said he would always carry the guilt of being unable to protect a boy who had come to the UK seeking safety and opportunity. “As Ahmad’s uncle, I will always carry the guilt that Ahmad had come to the UK, and I could not keep him safe,” he said, adding: “Ahmad we love you, we miss you and we will do for ever.” In court, he had asked the judge to consider the effect not only on those who loved Ahmad but also on the wider community of young refugees who look to Britain for refuge. The judge said he had read all the statements and accepted that the killing had reverberated well beyond the immediate family.

Franco, who spent part of his childhood in South Africa before returning to Huddersfield at 13, sat impassive as the minimum term was read. The life sentence means he must serve at least 23 years before he can be considered for release by the Parole Board; if freed, he would remain on licence for the rest of his life and could be recalled to prison. The court was told he had no previous convictions for violence of a similar nature but had admitted to carrying the flick knife in public. The judge said the combination of carrying a weapon, choosing to engage and then to escalate a brief street encounter into a lethal attack placed the crime in the most serious category.

The Crown Prosecution Service said the verdict and sentence reflected the principle that the public must be safe from those who carry blades on the streets and that consent or threat could not be conjured out of a passer-by’s accidental contact. “Ahmad was unarmed,” Wright said in court. “He didn’t have a chance.” Police said they hoped the conclusion of the case would allow Ahmad’s relatives to grieve without the strain of proceedings. “No sentence can ever bring back Ahmad,” Detective Superintendent Roebuck said, “but we hope seeing Franco jailed for many years today will bring some measure of comfort to a family who continue to grieve for his loss.”

As the courtroom emptied and the formalities ended, the images that anchored the trial—grainy clips from street cameras, the small motions of a hand moving to a pocket, the half-turn of a head at a stranger’s voice—retained a grim clarity. They recorded how a boy who had crossed borders to rebuild a life was drawn, in seconds, into a fatal arc of violence on a British high street. The law answered with the heaviest sanction short of a whole-life term. For a family planning for a future that will now never arrive, the hope lies, as they said, in the memory of a teenager who loved to help people and who believed he had found “the land of peace and the fulfilment of dreams.”